Levels of Measurement

Nominal vs. Ordinal vs. Interval vs. Ratio

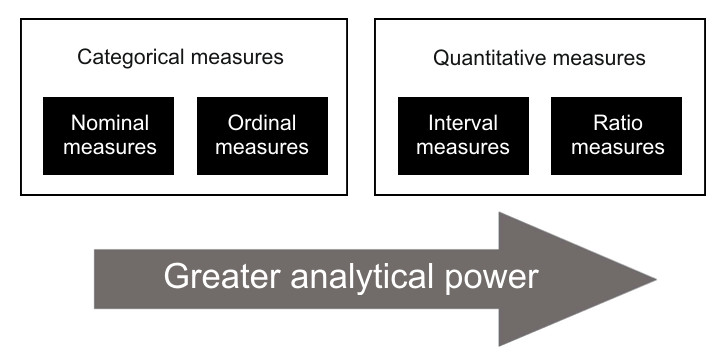

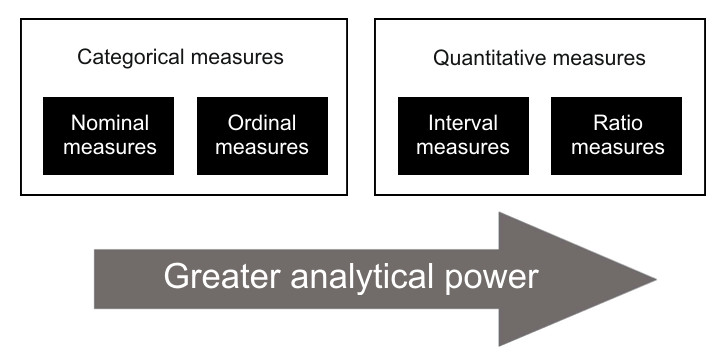

These four different types of measures are often referred to as "level of measurement," and they have this relationship:

To better explain these ideas, I will present them "out of order" from the table above.

Interval measures

In this type of quantitative measure, the values are measured in some sort of "unit" and the units are consistent up and down the scale. For example, the distance between 1 unit to 2 units is the same as the distance between 99 units to 100 units. As a result, we can say "distance" is meaningful on the scale.

e.g., The example that's often given for an interval measure is the Fahrenheit scale of temperature. All the way up and down the scale, one degree F means the same thing. Therefore, it's an interval scale.

e.g., The number of Google searches for our company's name that were made by people in the last seven days.

This example certainly fits the idea that the "units" are consistent at all levels of the scale. For example, the difference between 100 searches and 101 searches is the same as the difference between 1000 searches and 1001 searches. This example also meets the more stringent criteria for ratio measures described below, so strictly speaking it goes beyond interval measures to be a "ratio" measure.

e.g., In a marketing research survey, customers were presented with a ratings scale that allowed them to respond with a single number from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree).

This is slightly controversial as an example of an interval measure. Some experts argue that such a ratings scale doesn't yield interval measures. After all, what is one "unit" here? Who is to say whether the difference between 1 and 2 on this scale is the same as the difference between 9 and 10? Other experts argue that when placed under careful scrutiny, these sorts of scales behave very much like interval scales, and any differences from true interval scales are probably not important. As a practical matter, it is extremely common for researchers to treat data from these kinds of response scales as interval scales, and that's my rationale for offering it here as an example of an interval measure.

Ratio measures

Ratio measures are quantitative measures that meet the criteria for interval measures and go even further to meet one additional criterion: The "zero" on the scale actually means something. That is, the zero point is not arbitrary. Zero indicates a true absence of the construct.

e.g., The number of "likes" for our company's Facebook page

This is a count variable, and all count variables are ratio measures. The units (i.e., number of likes) is consistent all the way up and down the scale. Furthermore, zero on the scale has a meaningful interpretation. That is, if there are zero "likes," that's an absence of likes. And a bummer.

e.g., Total number of times this customer has transacted with us in the past

The number of transactions is an interval measure, and zero transactions has a valid interpretation as an absence of transactions, so this meets the criteria for ratio variable.

e.g., Our monthly advertising expenditures

This number could be zero or it could be higher. Pretty much anything measured in dollars is a ratio measure.

Here's another way to identify ratio measures: Would doubling the number imply that the underlying construct is doubled? If so, it's a ratio measure.

e.g., "Total number of times this customer has transacted with us in the past" does meet this criterion. For example, someone who has transacted with us 20 times has, indeed, transacted twice as often as someone who has transacted with us 10 times.

Notice the degrees Fahrenheit described in "interval measures" above does not meet this threshold. It's not right to say that 60° F is "twice as warm" as 30° F. Ultimately, the reason "double" doesn't work is because the zero on the scale is arbitrary.

For fans of physics: The Kelvin scale of temperature is a ratio scale because zero on that scale has a meaningful interpretation (i.e., "absolute zero" is 0° K and it represents no heat at all.) Thus, 300° K (about 80° F) is twice as warm as 150° K (about -190° F). Nifty, huh? Plus, when you say the average of the daily low temperature in Provo in January is 267° K, it sounds so much warmer than 22° F.

More importantly, please note the questionnaire ratings scale that is described in "interval measure" above does not meet this threshold. It's not right to say that someone who responds with 8 has a level of agreement that is "twice as much" as someone who responds with 4. All researchers would say such response scales are at least ordinal measures, most of them are willing to assume such response scales are interval measures, but practically none of them is willing to say such response scales are ratio measures.

Ordinal measures

This is a type of categorical measure. The measure's types or categories have an inherent order, but the distance between the categories is not uniform or consistent. Loosely speaking, ordinal measures are somewhat similar to interval measures and somewhat similar to nominal measures.

e.g., We have three segments of customers: (1) purchase rarely, (2) purchase moderately often, and (3) purchase very often.

These three segments vary on one dimension: frequency of purchase. They have an order (lowest to highest), but they don't seem to meet the criteria for interval measures. If we had a frequency measure such as "number of purchases per month" instead of a simple assignment into one of three group categories, we would have a ratio measure. But if we only have the assignments to the segment categories as described here, we have an ordinal variable.

e.g., In a survey, customers were presented with a list of problems they might have experienced. They were asked to describe the importance of those problems by rank-ordering the list in order of importance. The data show "1" for the most important problem, "2" for the second-most important problem, and so on.

Rank orders are always ordinal measures. A ranking is not an interval measure because we have no reason whatsoever to think the distance between, say, 2 and 3 is the same as the distance between 5 and 6. That is, there might be a huge difference in importance between 2 and 3, and there might be very little difference in importance between 5 and 6. Measuring with an ordinal rank will mask and obscure all those distinctions. We can't say 2 is "one unit higher" than 3. That is, 2 is clearly "higher" in importance than 3, but it's not "one unit" higher. Because the intervals aren't necessarily consistent up and down the scale, it's not an interval measure. That said, the rank has some information about the order. If we were to treat a rank as having absolutely no relationship whatsoever between the types, we would be ignoring information. In this example, 1 is more important than 2, and that's more important than 3, and so on. That's the ordinal aspect of the measure.

Nominal measures

This type of categorical measure is assignments to categories that have no ordinal relationship with one another. The categories are simply a collection of types.

e.g., The customer's location has been assigned to one of three categories: (1) the United States, (2) Canada or Mexico, (3) elsewhere in the world.

e.g., We have three segments of customers: (1) healthy, (2) social, and (3) environmentalists.

e.g., The customer's gender is male or female.